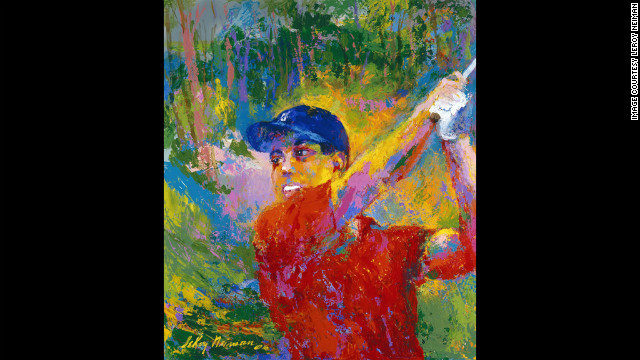

LeRoy Neiman, the flamboyantly mustachioed painter whose vivid

portraits of athletes and celebrities made him one of the best-known and

commercially successful American artists, has died. He was 91.

His publicist Gail Parenteau confirmed his death Wednesday without

disclosing the cause, the Associated Press reported. The New York Post

said in April 2010 that a vascular problem had forced the amputation of

Neiman’s right leg.

Neiman never won acclaim among experts and critics — entire books on

20th-century art don’t mention his name — but his post-impressionist

figurative paintings, sold in quantity as serigraphs, lithographs and

posters, delivered art to a mass audience.

For Neiman, the standard framed painting was just one of many

possible media. He made drawings and portraits for sporting-event

programs, Playboy magazine and Wheaties boxes, as well as huge public

murals such as the 56-foot (17 meters) “Summertime Along Indiana Dunes”

inside the Mercantile National Bank in Hammond, Ind.

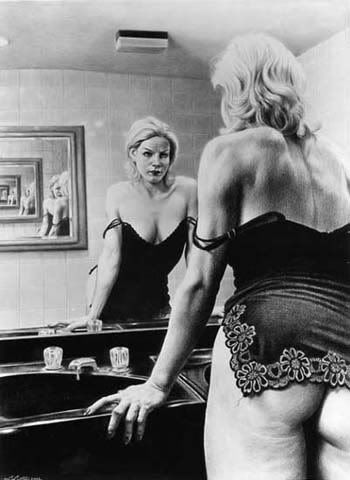

Among his lasting creations was the Femlin — a combination of the

words female and gremlin — that has appeared for decades on Playboy’s

joke page in long gloves, stockings, heels, and nothing else.

Though interested in all types of leisure activities, Neiman was drawn most intently to athletic events.

Sports, he wrote in 1975, “is all color and movement, a world of

numbers, flags and geometric surfaces. It is a universe of green, from

the gaming tables to the gridiron.”

Neiman drew and painted at six Olympic Games, had cameo roles in

three “Rocky” movies and saw his works displayed in the baseball,

basketball, football, boxing and tennis halls of fame.

His 1969 “Le Mans” — a color-splashed take on the French auto race —

drew $107,550 at a 2003 Christie’s auction, the top price ever paid for

one of his paintings, according to sale tracker Artnet.

Neiman’s colorful, representational style and use of celebrity

subjects gave him broad appeal among Americans. He combined the

real-life subject matter of the Ashcan School with the rapid brushwork

of abstract expressionism. Like Jackson Pollack, he used free-flowing

enamel house paint to imbue his paintings with a sense of motion.

His many subjects over the years included Martin Luther King Jr., the

Beatles, Leonard Bernstein, Rudolf Nureyev, Muhammad Ali, Frank

Sinatra, Arnold Palmer, Pele and the racehorse Secretariat, plus

strippers, stock traders and black-tied waiters at work in their various

places of business.

A globe-trotting celebrity in his own right, Neiman was often

photographed at sporting events in a white suit with a cigar in one

hand, his handlebar mustache impeccably groomed. He worked with

television networks so that his sketching was seen live, in progress, by

viewers.

He said his mission in art was “to investigate life’s social strata

from the workman to the multimillionaire.” One time he agreed to give a

painting to a plumber as payment for the installation of a sink: “Fair

exchange, my art for his.”

Neiman always professed to be unconcerned about criticism. “I struck a

chord. History will rate me with Andy Warhol, Norman Rockwell and Walt

Disney,” he said in a 1995 interview with the New York Times.

“I’ve got the public,” he told the Associated Press in 2007. “I don’t care about the critics.”

LeRoy Neiman was born on June 8, 1921, in St. Paul, Minn., though he

often put his year of birth as 1927. He joked that he had four important

prerequisites for an artist: starting life in poverty, coming from a

broken home, dropping out of high school and having an undistinguished

military career.

He was a young boy when his father, Charles Runquist, a laborer, left

his mother, Lydia Serline. Neiman would subsequently take the last name

of one of his stepfathers. Art and sports, particularly boxing, filled

his boyhood days.

Neiman enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1942 and spent three years in

Europe. A cook, he used his spare time to paint murals in mess halls. He

then worked on sets and murals for American Red Cross recreational

facilities in Germany.

Back home in 1946, Neiman embarked on formal art training, first at

the St. Paul Art Center and then, thanks to the GI Bill, at the Art

Institute of Chicago, where he began teaching figure drawing and fashion

illustration. He provided drawings for fashion ads that appeared in

magazines such as Vogue, Harpers Bazaar and Glamour.

Working as an illustrator at the Chicago department store Carson

Pirie Scott, Neiman made two acquaintances that would shape his life.

One was Janet Byrne, whom he would marry in 1957. He also became friends

with an advertising copywriter named Hugh Hefner.

When Hefner started Playboy in 1954, he recruited Neiman to

illustrate a story. That kicked off a long and fruitful affiliation.

Beginning in 1958 Neiman wrote and illustrated the Playboy feature “Man

at His Leisure,” for which he journeyed to sporting and social events

around the world.

A door to commercial success opened in the 1960s when Armand Hammer,

the wealthy oil magnate and art collector, began dealing Neiman’s

paintings through his Hammer Galleries in New York. In 1975 the Hammer

family created Knoedler Publishing to market Neiman’s serigraphs,

etchings, books and posters.

Beginning in the 1990s, Neiman took the matter of his legacy into his

own hands. He and his wife donated $6 million to Columbia University’s

School of the Arts in 1996 to create the LeRoy Neiman Center for Print

Studies, and $1 million in 1998 to create the LeRoy Neiman Center for

the Study of American Society and Culture at the University of

California-Los Angeles. In 2005 Neiman donated his papers to the

Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

The

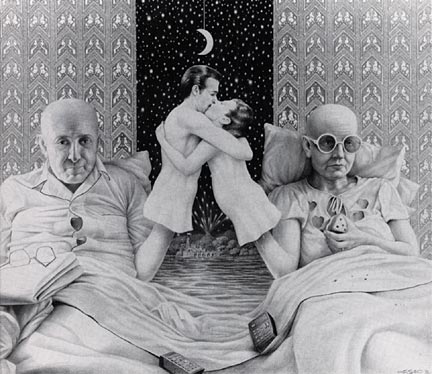

AmericanLondon. rie Lipton has had numerous one woman shows

in England, Belgium, Holland and America. She was previously

represented by the prestigious Vorpal Gallery, and has had her

work exhibited in both New York & San Francisco. She recently

had a major retrospective show at the Chamber of Pop Culture,

a fine art book of her drawings is planned for early next year.

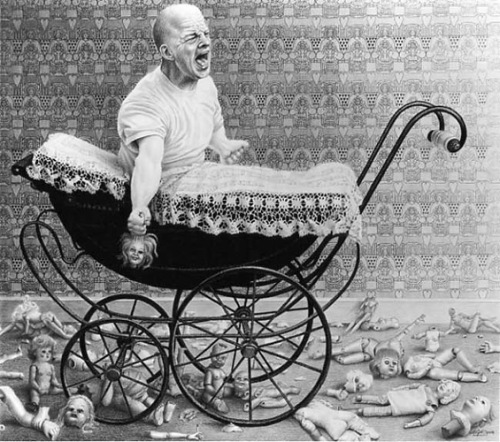

The

AmericanLondon. rie Lipton has had numerous one woman shows

in England, Belgium, Holland and America. She was previously

represented by the prestigious Vorpal Gallery, and has had her

work exhibited in both New York & San Francisco. She recently

had a major retrospective show at the Chamber of Pop Culture,

a fine art book of her drawings is planned for early next year.